Charting

NDisc from Sony to Philips to SuperFX to NEC

Even

though this site is supposed to be a 1990s style tribute to StarFox,

we need to get some SNES CD-ROM history sorted out. It’s too

easy to get confused with the stupid Sony debacle, the Philips

drive, the SuperFX, and the “32-bit”ness.

Even

though this site is supposed to be a 1990s style tribute to StarFox,

we need to get some SNES CD-ROM history sorted out. It’s too

easy to get confused with the stupid Sony debacle, the Philips

drive, the SuperFX, and the “32-bit”ness.

In

facial media youtube-r speak, let’s “EXPLAIN” this

“SHOCKING” and “INSANE” history!

The main objectives of this page are to:

Explain the

differences between 3 known Super NES CD-ROM accessories. And a

rumored fourth!

Explain why

Nintendo dumping Sony was NOT a mistake, and should have

happened earlier.

Give context why this was

important. The snazzy new CD-ROM hardware could have been a step

backward from cartridges.

There's actually a fantastic

Kotaku article that documents this saga very well except for a

couple of missing elements. And another on

nsider.

Back in the 1990s there were no news

websites to scour for this information. You had to dig hard between

the magazines, writing to Nintendo directly, hunting through patents,

and business news electronic periodical searches .

If one pieces together SNES CD-ROM

information in sequence, one gets a rare treat in this

industry -- outsiders able to witness the labored development of a

product as it changes to meet evolving needs of the marketplace.

Products evolve

and change frequently before coming to market, and not always in the

correct direction. For example, in recent years (circa 2019) Jez San

(of Argonaut fame) spoke of his efforts to

build a full-color VR system that was canned in favor of Virtual

Boy.

Obligatory Background

So what led up to

the CD-ROM era?

In 1982 Sony and Philips introduced the

"Compact Disc", so termed because it was much smaller than

laserdisc. Although it was envisioned as a general data storage

medium from day one, throughout the 1980s "CD" was more

synonymous with the Red Book audio format (audio CDs) largely due to

the format's cost.

As the

1990s approached the feasibility of marrying optical media and games

seemed imminent. The PC gaming crowd even invented a new marketing

buzzword, "multimedia"! It was a generic word

vaguely meaning "a combination of video, pictures, voice...."

but really just meaning "we now have a bulk storage device and

now we can make video games, too".

Growing Pains: Multimedia or Muddled Media?

Reality was another story. What value

did these expensive add-ons even provide?

1. Cost, although coming down, was still a

huge factor.

The 1991

Sears WishBook catalog, page 506, listed the original

TurboGrafx-16 CD-ROM2 attachment (a barebones drive with no games

and still requires the TurboGrafx-16 to attach it to) for $299.99.

Sega CD

(again, an accessory that requires investment in a Sega Genesis)

also cost US$300 when it was first introduced.

Nintendo promised a $200 CD-ROM

accessory with superior capability. The Electronic Gaming Monthly

editorial rabble always laughed and lambasted this as impossible. “A

32-Bit system wih Philips CD-I compatibility for $200 by the Winter

of 1993-1994? Come on Nintendo! How in the world are you going to do

that?” (Electronic Gaming Monthly, March 1993, Volume

6, Issue 3, page 16). They were unaware the declining cost of these

components. That low-power 32-bit chip was already on the market In

1991. Regardless, even a $200 accessory is still twice the cost of a

bare-bones Super NES ($99.99) in 1993.

2. When you suddenly have bulk capacity, at

costs multiplying that of the original console, what do you do

with it?

You can copy

lots of small games into the space. This is called "shovelware",

which no one wants to spend hundreds of dollars on a dedicated unit

for.

You can have

a normal size game and tack on some Red Book CD audio tracks. In

other words, enhanced audio, but no improvement elsewhere. In fact,

depending on the amount of RAM you have, this can actually downgrade

the rest of the game versus a huge ROM cartridge.

You can fill

the space with video, except:

You can't

fit enormous amounts of video even with compression. (Even

VCD format Hollywood movie fills 2 discs!)

You only

have 150KBytes/second you can pull from the disc, for both audio

and video. About 1 megabit/second.

You don't

have enough horsepower to run expensive MPEG1 algorithms on video.

(Even the Philips CD-I and 3DO consoles required expensive MPEG

hardware add-ons to support MPEG video. Again, talk about a

segmented market when you need an add-on for an already obscure

console.) Most video compression involved some form of lightweight

"cinepak" style routines and try to fit inside some small

window, often cutting as many frames as possible and as many colors

as possible to fit in the confines of the console in question.

Video

production is expensive. How does it benefit your gameplay?

Or you can spend lots of money making

an even bigger game, breaking it up into small chunks you can load

into RAM. This means your customers have to own the base console, an

expensive CD attachment, and still be willing to foot the bill for

an expensive CD-ROM game. Who cares if the manufacturing cost of the

disc is small if you still have many millions of dollars in

development cost to recoup? And again, now you have a smaller

audience of CD-ROM customers to divide that cost between.

3. What good is a huge bulk storage device

that you can only sip data through a straw? To be useful, suddenly

you need more RAM. And if you can afford enough RAM, by then you can

also afford a bigger cartridge! So then you're chasing your tail

again. Is your CD-ROM really an upgrade over the cartridge?

Your game

console can only manipulate so much data per frame. There's a limit

to how big your game level database will be and how many such levels

you can afford to produce.

Cartridge

ROM grows exponentially with time, doubling every 18 months with

Moore's Law. But once the CD-ROM and its RAM are finalized they are

set in stone and do not grow at all unless you left room for a RAM

upgrade.

If your new

cartridge is sufficiently bigger than your old CD-ROM RAM,

eventually you get to a point where the cartridge game can throw

more data per level than you can fit in RAM!

We've seen

this many times!

One example

was Street Fighter 2 on the TurboGrafx-16/PC-Engine.

The game and its 12 combatants took 20 megabits of cartridge space.

To load up 2 such combatants from CD-ROM would take more RAM than

the CD system had!

Electronic

Gaming Monthly (April 1993, volume 6, issue 4, page 50) ran an

article on this conundrum. Capcom considered releasing the

game as a cartridge + CD-ROM combination, where the game ran on

cartridge and streamed background music off CD. Obviously

this never happened.

This

scenario led to the TurboDuo "Arcade Card", which was a

RAM size upgrade. Unsurprisingly it was useful for porting other

such one-on-one tournament fighting games like SNK’s Art

of Fighting.

In later

years we saw it again with Mortal Kombat 3 on the Sony

Playstation. Shang Tsung's ability to morph into other

combatants required the game to pause just to load that new set of

combatant data into RAM.

The Neo-Geo

CD in 1994 had more RAM than the N64 had in 1996. Its entire

purpose was to load a usable amount of CD-ROM game data into a

virtual cartridge. It was ample enough to hold the early generation

Neo-Geo cartridge games (Magician Lord, Mutation Nation,

Last Resort, etc.) entirely in RAM (except for redbook

streamed audio remixes). But by this point all new large tournament

fighting games were hundreds of megabits.

Was it

really worth spending several hundred dollars for a CD-only system

just to play older games well? Those same older games that by this

point would cost much less to re-manufacture as new cartridges

with fewer/denser ROM chips in the first place!

And meanwhile now all of your new

games need to be developed with a full cartridge in mind (for MVS

arcade and AES system owners) and still be somehow able to fit

enough useful chunks into the RAM of the CD system?

Congratulations --- you just made game development harder, not

easier.

Nintendo Power volume 35 seemed as

eager as everyone. "How would you like to go one-on-one with

Michael Jordan?" they wrote on page 71. But it wasn't long

before Nintendo soured on what they saw. 9 months later, in volume

44, on Super Power Club extra, page 15, they spend paragraphs talking

about the need to improve the gaming experience over "cartridge

games on a disc".

Unbeknownst to most readers the SNES CD

effort had gone through at least 3 major product revisions by that

point! It was a major effort not only full of corporate politics

(that story is beaten to death now) but also to make a product stand

out not only against the competition but also against its cartridge

bretheren.

CONCLUSION:

An expensive CD-ROM accessory would have to be sufficiently capable

to justify its own existence for the duration of the console's

lifetime.

The Sources

Contemporaneous Periodicals

In the early 1990s most sources were in

printed magazines that ranged from "highly accurate" to

"highly speculative" to "highly opinionated".

Worse, they gathered juicy bits of news from their own undocumented

sources (frequently Japanese magazine correspondents) and presented

it as their own article. And while these articles were often accurate

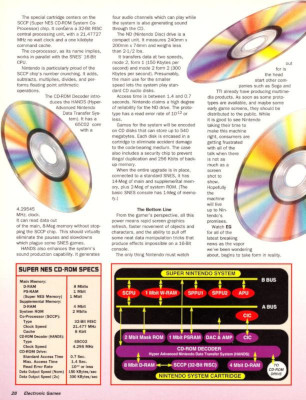

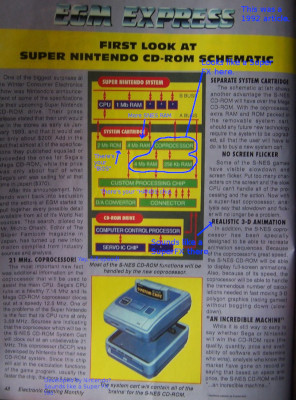

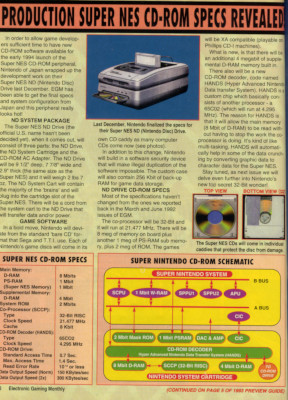

(e.g. Electronic Gaming Monthly's final block diagram (March

1993, Volume 6, Issue 3, page 52) matches the 1995 patent), they'd be

juxtaposed in the same issue with articles by Quarterman that

read like a foreign language rumor mill. Not unlike the Internet

of today! Some things never change.

Physical Devices

One of the greatest sources in recent years

was the discovery and teardown of the prototype Sony unit.

Patents

Electronic patent searches by website were a

novel thing by the mid 1990s, long after the CD unit was shelved. And

while patents can be controversial (or sometimes intentionally vague)

in their own right, generally a patent on a physical product requires

some sort of physical product or implementation before it can be

granted.

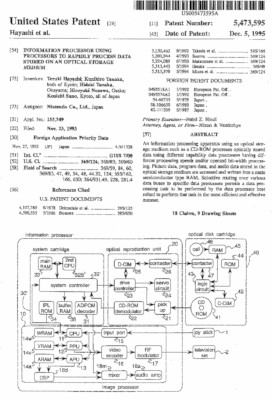

The patents for the Super FX (#5,357,604) and the final CD-ROM

add-on are both public.

Developer Documentation

In recent years Nintendo's CD-ROM developer

documentation was discovered. It confirmed the EGM block diagram and

details the XA format and its ADPCM compression. The most juicy

details (how to control the data flow from CD-ROM to HANDS) are still

missing.

Financial Analyst Reports, courtesy of

InfoTrac

There is a supreme irony that while the

video game industry struggled with CD-ROM, libraries around the

country used them very effectively as a text-only data archive called

InfoTrac. One of

the greatest sources on the Super NES CD-ROM product was itself

archived on this CD-ROM system. Think of InfoTrac as a self-contained

world-wide-web and search engine all in one, except the searches were

periodicals listings. Most of the search results were abstract

summaries of the text (occasionally whole articles). By academic

standards that technically means relying on InfoTrac

without finding the original article is a dreaded Secondary

Source, but it's about as close to

authoritative as you can get these days.

The other irony is that our big source here

is from Lehman Brothers, a once large company that imploded

spectacularly in the 2008 financial meltdown. So good luck finding

the original sources.

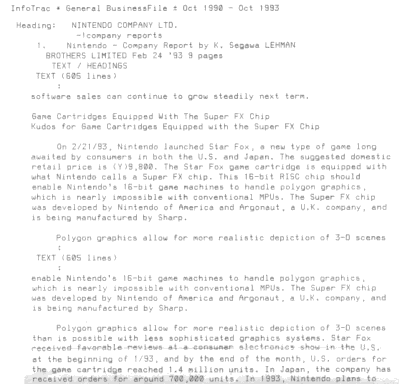

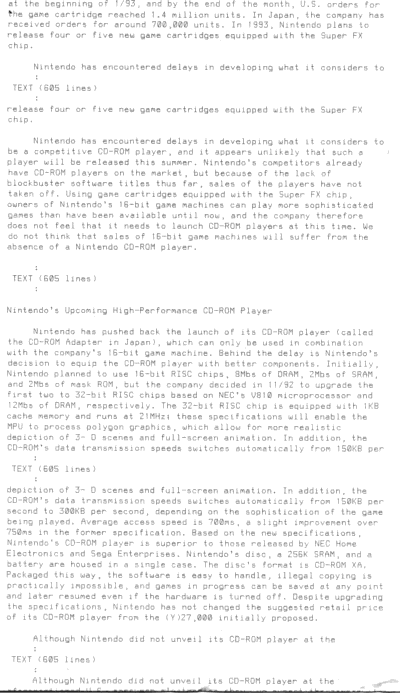

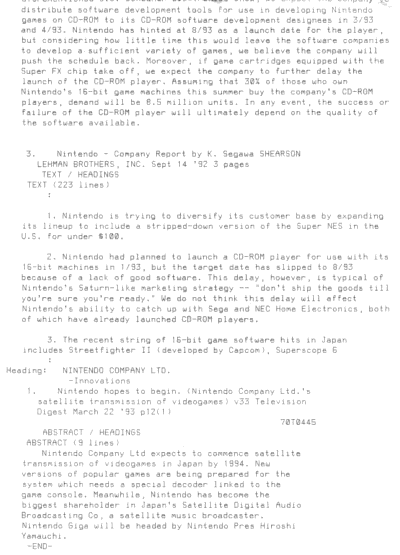

A financial analyst named K. Segawa

authored a Nintendo company report on Feb 24, 1993 and it was

captured in the InfoTrac General BusinessFile October 1990 -

October 1993. This one details the 32-bit upgrade.

The same author

wrote an earlier company report on September 14, 1992 with a

paragraph mentioning launch dates for the previous (pre-32-bit) unit.

I have scans of

these InfoTrac summaries here. Click for larger sizes.

At Last The Contenders: SNES CD/Super

Disc/N Disc Survey

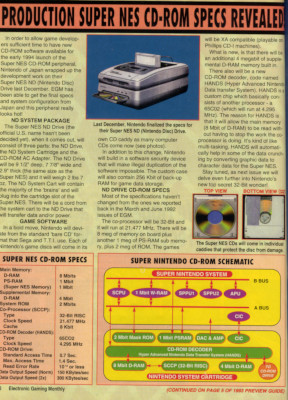

There are at least 2 CD-ROM base units (the

Sony unit and the newer Philips unit). Strictly

speaking, there might be 2 Philips drives. We know average access

time improved from 750ms to 700ms, per the Lehman Brothers

report.

At the end of the

day, the CD-ROM drive is just a CD-ROM drive, with the Philips unit

being superior both in speed (it supports 2x speed) and disc format

(it also supports XA format, if desired). The Philips unit also had

those cute CD caddies with the built-in save RAM, which is smart for

a number of reasons. But again, it's all bulk storage. It's important

to the success of the product, but alone it doesn't elevate any of

the machine's capabilities.

There are at least 3 system cartridges that

hold RAM, and sometimes other processors. Under this model, the

CD-ROM fills the cartridge up with data, and the SNES sees it as a

normal cartridge. It also means you can (theoretically) upgrade the

system by upgrading the system cartridge, much as what NEC/TurboTech

did for the PC-Engine/TurboGrafx-16 Super CD-ROM2 and Arcade

Cartridge upgrades, and much as Nintendo did for the 64DD (which is

just another cartridge underneath the Nintendo64).

Most of the system's magic is in the system

cartridge. This, above all else, makes or breaks the product.

This article is going to demonstrate how pathetic the Sony system

cartridge was, and why it had no future.

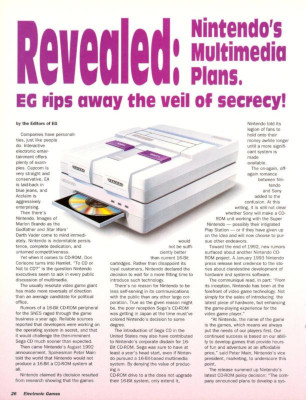

Ewww the Sony

So let's start with the embarassment of the

Sony system cartridge:

Sony

Play Station System Cartridge, 1992

|

|

PROOF:

|

We have the teardown

video showing the contents

|

ROM:

|

There is a boot ROM (think of it as a

"BIOS", or in console terms "IPL") and it

holds all the pretty pictures for the splash screen and

initializing the system. There's no magic here. Every system

cartridge will have some flavor of this.

|

RAM:

|

There are 2 SNES "WRAM" custom

DRAM chips, which means 2 megabits (or 256 KBytes) of RAM to hold

data from the CD. (Unclear how this is mapped and whether or not

the SNES can read these at 3.57 MHz or 2.68 MHz like its internal

RAM is.) This is the first huge disappointment. It proves the Sony

unit is more or less just a TurboDuo, scarcely able to

buffer up 1 second of read data from the drive, let alone do much

with it.

|

Backup RAM:

|

All game saves (for your entire CD game

library) must fit on the battery-backed 64 kilobit (8 KBytes) SRAM

inside the system cartridge. This may seem small for RPGs, but

it's identical to how the later Neo-Geo CD works and those

small save states do fit fine. I've never run out of space on my

Neo-Geo CD, but I've also never had to bring it over to a friend's

place to share my game save state. To bring a saved game to

another location, you need to bring the CD disc and your Sony

system cartridge.

|

Coprocessors?

|

NONE! This is the second big

disappointment. Did they really expect the SNES CPU to decode

video and run a game at the same time? You could, but then it'd be

no different from existing cartridge games like Out of This

World. Where's the upgrade? What did you spend all of that

money for if you got nothing new in return?

|

Audio?

|

Red Book CD-DA audio on the side.

|

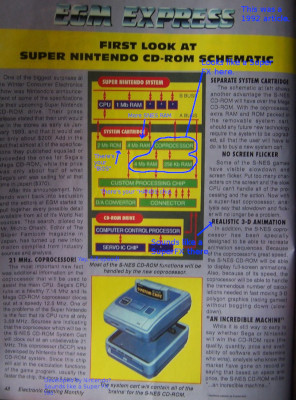

Philips Drive + Super FX

Now we move on to the first generation

Philips model, promised to be $200 with serious performance upgrades.

This is actually the system cartridge we know the least about

because our sources are more indirect. We have to read a little

between the lines. You also wouldn't believe the incredulity in

Electronic Gaming Monthly editorials (EGM editors always hated

on Nintendo back then), but they were publishing specs as they

received them. Nintendo was always vague about the "coprocessor"

in the system cartridge, but it's painfully obvious that it was

indeed a Super FX. What else did they have at their ready

disposal that ran at that speed, did 3D, already worked with the

system, and had that 3-way bus design? All they had to do is replace

the ROM with a RAM that could be filled by what is also obviously an

ancestor of the "H.A.N.D.S." chip.

It's worth noting we have some conflicts

between these sources:

2 magazine

articles (Electronic Gaming Monthly and Nintendo Power)

hint at 8+1 == 9 megabits of total RAM

One other

Electronic Gaming Monthly article says 4+4+0.25 megabits

total RAM.

The Lehman Brothers article

indicates a total of 10 megabits of RAM, with no mention of how it

was distributed. A logical method would be 4 (HANDS) + 4 (SuperFX

"ROM" bus) + 1 (SuperFX "RAM" bus) + 1 (SNES

exclusive). A similar split-model SuperFX memory map is

well-documented elsewhere, although never really employed in

practice due to cost. (Nintendo’s own SNES development

manual documents a 16 megabit (SuperFX ROM) + 1 megabit (SuperFX

RAM) + 48 megabit (SNES ROM) + 1 megabit (SNES RAM) configuration

that was obviously never used.)

Any of these is feasible. The SuperFX

will happily take up to 1 megabit of its own work RAM, and could

easily take 4, 8, or later on 16 megabits on its ROM bus. It's

evident from the EGM schematic that we probably ended up with

4 megabits of HANDS memory (used for audio, CD buffering work, CD

packet error correction, or whatever else needed), 4 megabits of

memory mapped into the SuperFX's ROM space, and 1 megabit of SRAM

mapped into the SuperFX's RAM space instead of 256 kilobits (FYI

StarFox has 256 kilobits.). That would match the "9

megabit" articles and make the most sense for decompressing

larger 8-bit images. All of this is visible to the SNES as well,

provided everything is set up correctly.

Regardless of the exact RAM configuration,

this system cartridge is quite nice! In fact, it soundly kicks Sega

CD tail. Remember the Sega CD was often called a "downgrade"

for the Genesis because it gave the Genesis only 2 megabits of RAM

plus 4 megabits hidden behind a second 68000 CPU (so, 6 megabits

total, but not all directly visible). Firstly, we instantly benefit

from a 2x CD-ROM drive versus the 1x Sega CD. Also, not only is the

total RAM quantity bigger than the Sega CD, but the SNES can access

all of it with less fuss. We also get a faster coprocessor (SuperFX

over 68000).......at the expense of wide development tool support. I

must concede it's easier to get tools for a popular Motorola chip

than a custom chip. Because the Philips XA format requires ADPCM

audio support, undoubtedly this HANDS chip ancestor also had

the 4 extra ADPCM sound channels the final version had (hence the 4

megabits local RAM), so we also get a clear sound upgrade beyond just

streaming Red Book CD audio.

In fact, the only down side of this

configuration was imminent obsolesence. StarFox itself was on

the horizon. If SuperFX cartridges were already in the wild, what

more could CD-ROM offer beyond bulk storage and extra audio? In fact,

I've always suspected this was why Nintendo was so quiet about this

system cartridge. The marketing department wouldn't want to detract

from either product. StarFox is both a teaser product to whet

your appetite for more, and also a competitor.

Philips

Unit "SuperFX" System Cartridge, 1992 (anticipated

launch: January 1993, pushed back to August 1993)

|

|

EVIDENCE 1:

|

We have the SuperFX patent itself.

#5,357,604, granted finally October 18, 1994. This is evidence,

not proof, as patents are intentionally written as vaguely as

possible to cover broad use cases. Usage in a CD-ROM environment

is specifically detailed in columns 7 and 8.

|

EVIDENCE 2:

|

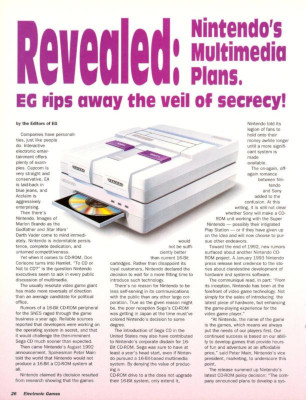

We have the first Electronic Gaming

Monthly article, from June 1992, issue 35, page 48. This issue is available from Retromags.

|

EVIDENCE 3:

|

We have the second Electronic Gaming

Monthly article. Electronic Games, April 1993, which discusses the upgrade from "16-bit" to "32-bit". This can be downloaded from Retromags.

|

EVIDENCE 4:

|

We have the Nintendo Power article,

volume 35, pages 70-71. This makes no mention of processors, and

in one sentence mentions "8 megabits" and in another

mentions "9 megabits". Either this was a misprint or

they are factoring in the SNES’s own 1 megabit internal

WRAM, or they are factoring in an extra megabit for the SNES, or

they are factoring in an extra megabit for the Super FX's working

RAM space.

|

EVIDENCE 5:

|

We have the Nintendo Power article,

volume 43, page 6. The sudden announcement of a 32-bit system

cartridge, claiming that "16-bit" wasn't good enough.

That's reverse evidence that we did, in fact, have a middle of the

road system cartridge like this one.

|

EVIDENCE 6:

|

We have the Feb 24, 1993 Lehman Brothers

financial analyst article by K. Segawa that specifically mentions

the upgrade from "16-bit RISC chips, 8Mbs of DRAM, 2 Mbs of

SRAM". So that implies we had something like 10 megabits in

this era. The distribution is unclear. 4+4+1+1 would be sensible.

(4 for HANDS, 4 for SuperFX, 1 for SuperFX, 1 for SNES)

|

ROM:

|

There is a boot ROM (think of it as a

"BIOS", or in console terms "IPL") and it

holds all the pretty pictures for the splash screen and

initializing the system. There's no magic here. Every system

cartridge will have some flavor of this.

|

RAM:

|

There is a 4 megabit RAM for each processor,

with 4 megabits taking the place of the Super FX ROM, and most

likely 1 megabit of RAM for the Super FX to work with. The types

of these memories (DRAM, SRAM, PSRAM) are unstated. Normally Super

FX RAM is SRAM but it can accept DRAM if needed.

|

Coprocessor 1

|

Super FX According to the articles,

apparently the full-speed 21.477 MHz flavor as well.

|

Coprocessor 2

|

Some early version of HANDS Something

has to manage the CD-ROM drive and its XA filesystem, fill up the

audio RAM, fill up the Super FX “ROM” bus, and play

sounds from audio RAM. Note, however, that in this era HANDS would

not need to convert bitmap graphics to bitplanes yet, as the

SuperFX already has hardware to do that inside.

|

Audio?

|

Judging from the EGM schematic, this looks

conspicuously like the later HANDS chip (described below), so most

likely it had the same 4 on-board ADPCM channels and the 65C02 CPU

to control them, sent through the cartridge analog input ports to

be mixed with the SNES audio.

|

Philips Drive + 32-bit NEC V-810

At last, what we presume to be the final

system cartridge! And what a beauty!

In total we would have doubled the combined

memory of the Sega CD.

We would have a clear improvement in audio

over the Sony drive, as now we have the XA filesystem and 4 extra

ADPCM channels in addition to the CD audio.

The V810 would have far eclipsed the Sega

CD’s Motorola 68000, probably about an order of magnitude on a

good day depending on how we hammer the memory bandwidth. It had

standard assemblers and debuggers, and was also a compiler-friendly

CPU that for the first time would have enabled C language. (No one

used C in consoles then, even on the 68000 which also had C

compilers.)

In fact, the V810 even had an FPU (floating

point math support) which even the later PlayStation CPU did not

have, although realistically this is academic as most games were not

big floating point math users and the V810's FPU wasn't particularly

fast.

The V810, which is a low-cost 32-bit RISC

design, did not have a huge instruction cache, but it was still

double the size of the Super FX instruction cache, and far better

than none on the 68000. We don't know the RAM bandwidth, but it's

most likely larger than the Super FX in aggregate.

Versus the Super FX, we do lose a few

specialty functions. We lose the ability to read from one bus and

write to another in parallel, and we lose the dedicated pixel "PLOT"

function that hid complex address calculations from the programmer.

On the Super FX you can just think in terms of (X,Y) coordinates and

it can figure out what data you mean regardless of 2-bit, 4-bit, or

8-bit pixels, but on the V810 it's all up to you to figure it out.

At this point the programmer is also now

faced with the bewildering task of managing the symphony of 4 very

unique CPUs (the 65C816, the SPC-700, the HANDS chip, and the NEC

V810) and continuous data flow between them. Certainly no less

herculean a task as coordinating two Motorola 68000s, a Z80, and 2

SH-2s with a 32X and Sega CD. But this was indeed the

era (e.g. the twin SH-2 Sega Saturn) where John Carmack

lamented about wishing for just one good CPU.

Philips

Unit 32-bit "NEC V810" System Cartridge, Designed:

November 1992, Announced: early 1993 (intended launch.....sometime

in late 1993 or early 1994)

|

|

PROOF 1:

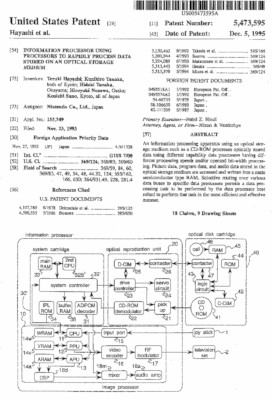

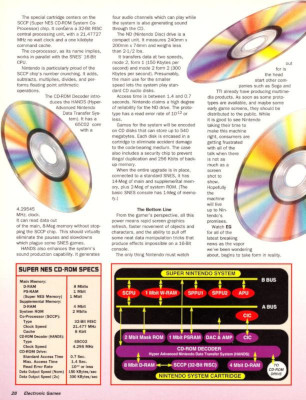

|

We have the final patent itself, finally

granted in December 1995. It is #5473595. This patent details the bus widths of each memory and the switching operations of HANDS.

|

PROOF 2:

|

We have a first round of the developers

documentation from Nintendo, 1993.

|

PROOF 3:

|

We have the Lehman Brothers business

article written by K. Segawa.

|

EVIDENCE 4:

|

We have the German magazine article.

|

EVIDENCE 5:

|

We have the Electronic Gaming Monthly

article, March 1993, volume 44, page 52.

|

EVIDENCE 6:

|

We have the Nintendo Power article,

volume 43, page 6 casually mentioning the upgrade. "Just in

case you haven't heard." Again, the clear intent was to

differentiate the CD-ROM accessory from cartridges at the time.

|

EVIDENCE 7:

|

We have the Nintendo Power article,

volume 44, in the subscribers' only special, writing at length

about both the Super FX and the future 32-bit CD-ROM system as if

they were now separate things (which they are).

|

ROM:

|

There is a 2 megabit (256 KByte) boot ROM

(think of it as a "BIOS", or in console terms "IPL")

and it holds all the pretty pictures for the splash screen and

initializing the system. There's no magic here. Every system

cartridge will have some flavor of this. You *could* hide a few

helper routines if you wanted to find a way to backdoor load them

upstream somehow, but doing so would be of limited value.

|

RAM:

|

HANDS has a 4 megabit PSRAM for its use

(audio, etc.). The V810 has an 8 megabit (1 MByte) DRAM, fillable

and readable by HANDS. And the SNES CPU gets another 1 megabit

(128 KBytes) just to itself.

|

Coprocessor 1

|

NEC V810 This 32-bit RISC CPU was

later used (in slightly different form) in the Virtual Boy

and also the NEC PC-FX. The Virtual Boy

implementation uses a 16-bit external bus to save cost, but is

also customized with a few tweaks, including a lower-latency

multiply operation that matches the cycle count of the Super FX

(16-bit x 16-bit) multiply. That seems like an unusually specific

addition, and one wonders if it was originally meant for this unit

so as not to lose multiplication performance by moving from the

Super FX to this chip. Normally V810 (32-bit x 32-bit) multiplies

are 13 cycles. According to the Super NES CD ROM patent,

apparently this V810 was going to have a 32-bit bus to its memory,

and, like the PC-FX version, this one ran at 21.477 MHz. It

is unclear to me how cleanly the 32-bit bus could be implemented

in such a cramped cartridge housing unless the V810 and HANDS were

housed in the same chip. Either way that was going to be a dense

cartridge.

|

Coprocessor 2

|

HANDS Something has to manage those

bus activities, fill up the NEC V810 RAM (how would this be

arbitrated between them?) and pull compressed audio out of RAM,

contain the on-board 65C02, etc. Also, this final HANDS will need

to convert bitmap graphics (that the NEC chip understands) to

bitplanes (which the Super NES understands) because the V810 has

no dedicated hardware for this and why bog down the CPU with this

task? Similar bitplane conversion hardware also later made an

appearance in the SA-1 coprocessor for the same reason, which

otherwise bears no resemblance to anything here. The 65C02 inside

HANDS runs at 4.295 MHz, and it's not clear by what bank switching

system this 8-bit CPU would access the entire 4 megabit region of

local memory.

|

Audio?

|

HANDS supports 4 on-board ADPCM channels and

the 65C02 CPU to control them, sent through the cartridge analog

input ports to be mixed with the SNES audio. The ADPCM data can

come from either the local 4 megabit memory and/or streamed off

the disc. And here's where the Philips XA format becomes useful,

too. If you have both streamed data (video or otherwise) and audio

that need synchronization, they can be stored together as part of

the XA format and the audio can be processed in parallel with the

data.

|

So now let's put

all of this in context with the competitive landscape:

CD-ROM

ADD-ONS FOR

|

NEC

TurboGrafx-16/PC-Engine

|

Nintendo

Super NES (Sony CD-ROM) (1991-1992 vintage)

|

Nintendo

Super NES (Philips CD-ROM + SuperFX) (1992-1993 vintage)

|

Sega

Genesis/MegaDrive

|

Nintendo

Super NES (Philips CD-ROM + 32-bit V810) (1993 vintage)

|

SNK

Neo-Geo

|

Vintage

|

1988-1994

(various)

|

1991-1992

|

1992-1993

|

1991-1992

|

1993

|

1994

|

Additional

RAM (not including backup)

|

512

kbit (64 KByte) for CD-ROM2 (1988/1990)

or

2 megabit

(256 KByte) for Super CD-ROM2 (1991/1992)

or

18 megabit

(2.25 MByte) for Arcade Card (1994)

|

2

megabits (256 KBytes)

|

8

megabits (1 MByte) + either 256 kbit or 1 megabit SuperFX RAM

|

6

megabits (0.75 MByte) + 512 kbits (64 KB) in total; 2 for Genesis,

4 for coprocessor only, rest for ADPCM sound decoder

|

13

megabits (1.625 MByte) in total; 1 for SNES, 4 for HANDS, 8 for

V810

|

56

megabits (7 MBytes) in total across all cartridge buses

|

Coprocessors?

|

None

|

None

|

Yes.

2: HANDS + SuperFX

|

Yes.

Supplemental Motorola 68000 and sound decoder

|

Yes.

2: HANDS + V810

|

None

|

CD-ROM

speed

|

1x

|

1x

|

2x or

1x

|

1x

|

2x or

1x

|

1x

until Japan-only CD-Z

|

Audio?

|

Disc

Streaming + 1 ADPCM channel

|

Disc

Streaming

|

Disc

Streaming + supplemental 4-channel HANDS ADPCM decoder

|

Disc

Streaming + Supplemental 8-channel RF5C164 ADPCM decoder

|

Disc

Streaming + supplemental 4-channel HANDS ADPCM decoder

|

Disc

Streaming

|

Backup

memory?

|

Built

in to TurboDuo (not transportable)

|

Built

in to cartridge (awkward but portable)

|

Built

into disc caddy (portable)

|

Built

in and optional memory cartridge.

|

Built

into disc caddy (portable)

|

Built

into console (not transportable)

|

In this era, any Nintendo CD-ROM accessory

has 2 chief competitors to fend off: 1. the outside competition and

2. the ever-growing cartridge itself.

The original

Sony CD-ROM accessory stood no chance of lasting in the market. It's

just a TurboDuo! By 1993 we had 16 megabit cartridges with eyes

toward 24 and 32 by the end of 1994. Did we really need to limit

game developers to loading no more than 2 megabits at a time off a

disc?

The original

Sony CD-ROM accessory featured no coprocessors of any kind at a time

when Nintendo was already working with Argonaut on what

became the SuperFX. That meant that cartridges were growing

in both size and capability while the CD-ROM just had (slow)

bulk storage behind it.

The Philips

CD-ROM + Super FX combination was pretty solid! This would fare well

against the Sega CD.

The

Motorola 68000 is far easier to develop for, with more tools behind

it. However, the SuperFX is considerably faster when treated right.

It would be a great tool for the same uses as that 68000 ---

software graphics decompression, sprite scaling, sprite rotation,

etc.

Nintendo's

unit would have far more RAM available for sound than Sega CD.

Great for beefy, bulkier sound effects.

Nintendo's

unit would share 4 megabits of RAM directly (and transparently)

between the Super NES itself and the SuperFX, so you could use it

however you needed to.

Nintendo's

drive was faster when called to be so (i.e. not when streaming

audio).

The Philips

CD-ROM + V810 combination was really solid! This would surpass the

Sega CD. At last we might have a unit with a few years of

life in it.

The V810 is

faster than the 68000, compiler-friendly, and had official

toolchains at the time.

The even larger RAM could buffer up

more data. The V810 could be used as a graphics decompressor or

even run game logic if desired. These are things that weren't quite

cheap enough to build onto a cartridge (yet).

Was There a Fourth CD-ROM?

Short answer: NO!

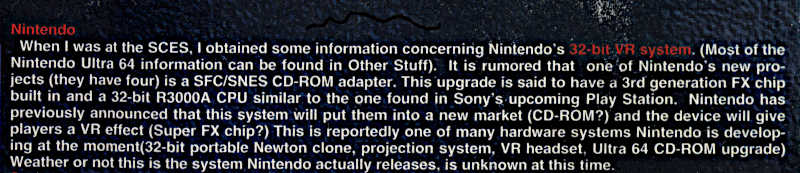

If you read

Diehard Gamefan, August 1994, Volume 2, Issue 9, page 157, you

came across this perplexing rumor.

As tantalizing as the idea

may be (having a beefy CPU to run a game engine and a “Super FX

3” to draw the graphics), at that point you might as well just

make a new system from scratch or else you just have another Sega

32X.

Imagine the chaos of programming the SNES (2 CPUs) and an

R3000A and a “Super FX 3” and coordinating it all. And

fitting it physically into a cartridge. What a mess. And in the end

you’re still limited by the VRAM and DMA performance of the

SNES anyway.

Indeed, I think this author just got some wires

crossed and is confusing the Super NES CD-ROM effort with the

aforementioned Argonaut stereoscopic display system. That fits all

of the other details of the story: “new market”,

“projection system”, “VR effect”, “VR

headset”.

Ultimately, this Argonaut VR project was

scrapped for the Virtual Boy instead. My suspicion is political

expediency. When the CD-ROM project was cancelled, NEC lost

potential sales on its V-810. And yet this was the same NEC

that was contracted to build chips for N64. Better to keep NEC

happy and sacrifice Argonaut instead? Not to mention a

project to keep your in-house engineers occupied while their other

foreign-designed (Silicon Graphics, Inc.) console made

progress.

The final patent for Nintendo’s

CD-ROM never makes any mention of such things either.

Let's Compare the CD-ROMs Against the

Tournament Fighters

For this example let’s use Rare’s

1995 Super NES port of Killer

Instinct. It was a 32-megabit

cartridge with no special hardware at all. We all knew it was cut

down from the arcade original, and yet it was very well-received in

spite of this. It made a great tide-me-over while we waited for the

Nintendo 64 and it played well despite its obvious limitations.

The

game features 11 combatants.

We can’t dive too deeply into

the guts of this game here. For certain there is plenty of generic

stuff inside: the main program, the sound driver to play back music

scores, common title screen and character select screen graphics, and

of course all of the narrator combo announcements like “Super

Combo!” or “Monster Combo!”. I don’t know

how much that all takes.

So let’s for now assume 30

megabits divided by 11 or just under 3 megabits per character.

This

is all armchair back-of-the-napkin arithmetic.

And that 3

megabits includes: one or two background levels, music score,

character sound effects, character data and graphics (undoubtedly

compressed somehow), and each character’s victory pose and

game-ending story scenes.

Sony CD-ROM

If we ported Killer Instinct onto the Sony

CD-ROM, the only tangible gains would be:

1) We can stream the

original arcade audio off the CD-ROM. This is good for quality (but

adds lag seeking tracks). That saves the SNES audio memory to hold

the sound effects.

2) We can leave the victory and game endings

on the disc (maybe even as short videos or simple animations!) as

they can be loaded as-needed. The result is they can be bigger and

take more space. Again, disc seeking lag is still a factor.

We can load the background graphics and

sound effects to the SNES’s own audio RAM and video RAM

directly. Maybe we can load the main program to the SNES’s

internal WRAM and have some room to spare if we are lucky. But since

that system cartridge just has 2 megabits of RAM, we have maybe only

1 megabit per combatant left to fit all their moves (graphics and

data).

It is hard to see this as a real win over the

cartridge! The in-game play is probably already compromised.

It’s

not even clear that all of the combo announcements would fit anywhere

in any of the RAMs to load into the SNES audio memory when needed.

(I don’t know how much space those take.)

The overall footprint of the game would be

much bigger than the SNES cartridge (because the audio tracks and

maybe the game endings could take up lots of space) but the in-game

action feels worse -- like maybe 1 or 2 megabits per

character times 11 characters, or about 22 megabits in total.

It

feels more like a DOWNGRADE.

So would this $200 machine really be an

“upgrade” to an SNES in 1992 or 1993? Only to be outdone

by a cartridge in 1995?

That’s fundamentally why this was

such a dead-end design.

Philips CD-ROM + Super FX

The Philips CD-ROM + Super FX system cart

combination already helps us.

Again, we gain:

1) We can

stream the original arcade audio off the CD-ROM. This is good for

quality (but adds lag seeking tracks). That saves the SNES audio

memory to hold the sound effects.

2) We can leave the victory

and game endings on the disc (maybe even as short videos or simple

animations!) as they can be loaded as-needed. The result is they can

be bigger and take more space. Again, disc seeking lag is still a

factor.

3) And now we also have roughly 4 megabits of

audio memory, assuming a little overhead for other activities that

HANDS might perform. (HANDS has supplemental ADPCM decoder channels,

which are required by the XA format, so you might as well use them

while streaming the background audio off the disc, right?) With any

luck, hopefully this can hold the combo announcements and leave room

for better quality character sound effects. And you can still play

hits and smacks on the SNES audio itself.

4) And now we have

roughly 4 megabits of storage on the Super FX (minus a little program

code overhead). We can also use the Super FX to do whatever graphics

decompression duties might be useful.

So now we can bat somewhere in the range of

3-4 megabits per combatant for the in-game action, or about 33-44

megabits total. Again, not counting the audio or game endings or

victory animations. The in-game action should be about equal to the

cartridge, and maybe a little faster with the FX doing decompression

for us.

Just about everything (audio, character graphics, combo

announcements) ought to be as good or better.

And that’s

why this unit starts to shine.

Furthermore, data

loading off the disc COULD be double-speed, although audio streaming

still has to be 1x. And skipping around to load up characters can

still be laggy.

Still, I hope it’s clear that this unit

just beat the pants off the Sony drive.

Philips CD-ROM + NEC V-810

Virtually the same scenario as

above.

Admittedly now we’ve traded out the Super FX for

the NEC V-810. We lose dedicated pixel plotting hardware for a more

general-purpose CPU, but it’s beefy enough. It could probably

run the whole game itself if we wanted to, meaning faster action

everywhere.

But now we’ve also got even more local RAM

hooked up to it. A portion of it is required to hold its program

code and work space. So, just guessing if we have 7 megabits left

over….

That becomes about 3.5 megabits of graphics + 1-2

megabits audio per combatant or about 4.5-5.5 megabits each.

Or

the equivalent of a 49-60 megabit cartridge plus room for audio and

ending animations.

So here, if you are willing to put up

with CD-ROM lag, you can get a genuine upgrade over the cartridge.

It would never match the arcade original, but it’d be nice!

...But For How Long?

We should have seen 64-megabit Super NES

cartridges. There are a number of ways to map that much space on the

console. Even the SA-1 can do it.

However, we never got

any Super NES games that big because:

1) 64-megabit ROMs were late to market.

Moore’s Law is not perfect and there are occasional hiccups.

This hiccup hurt us.

2) The capacity was being hoarded for the

first round of Nintendo64 cartridges, which ended up not arriving to

market before late 1996 anyway.

3) Developers were already

moving to the new consoles.

But if we DID have a

64-megabit cartridge back then it would have given fresh competition

to the above examples. Especially if bolted to the various special

chips Nintendo had at the time.

With Rare porting Killer

Instinct 2 for the Super NES (which was in development and

cancelled), one could have dreamed for such a configuration. The

cartridge they used was never confirmed.

Back

Even

though this site is supposed to be a 1990s style tribute to StarFox,

we need to get some SNES CD-ROM history sorted out. It’s too

easy to get confused with the stupid Sony debacle, the Philips

drive, the SuperFX, and the “32-bit”ness.

Even

though this site is supposed to be a 1990s style tribute to StarFox,

we need to get some SNES CD-ROM history sorted out. It’s too

easy to get confused with the stupid Sony debacle, the Philips

drive, the SuperFX, and the “32-bit”ness.